Fount™ Clinician

Module 2

Formulation and Designing Effective Treatment Plans

Hello and a welcome back to Fount Clinician! I hope you had a fantastic time exploring Module 1, where we dived deep into the art of comprehensive assessment and discovered how crucial it is in achieving positive client outcomes. I genuinely believe that conducting thorough assessments is the key to unlocking the best possible outcomes for our clients. By paying attention to those subtle yet crucial clues, we set the stage for meaningful transformations.

Now, I'm excited to share Module 2 with you. We will start this segment by learning about two imprtant therapeutic tools which, based on the Fount Therapeutic model, we will need to have in our therapeutic toolbox. These tools are:

Emotion or interoceptive exposure for reducing the presentation of emotions in the body

Imagery work for cognitive reappraisal and the shifting of core beliefs.

We will learn about these in some depth.

Next we will circle back to our good old friend Maslow's Hierarchy of needs! Continuing on the theme from the previous module, we will learn about a system of diagnosis and treatment that draws inspiration from this framework. This approach will help you tailor your therapeutic interventions to meet the unique needs of each tier of Maslow's Hierarchy of needs.

Finally, we will conclude this module by looking at practical steps to run a sucessful therapy session. Module 2 will be narrated by Michelle, a fresh voice that will be guiding you through the content! Rest assured, I'll be back for the concluding remarks to wrap up our learning adventure.

Alright, my fellow Fount Clinicians, let's jump right into it! Let's dive into Module 2 and take our therapeutic skills to the next level! Happy learning!

Curriculum

Please complete the following sections, in a chronological order. It should take up to 3 hours.

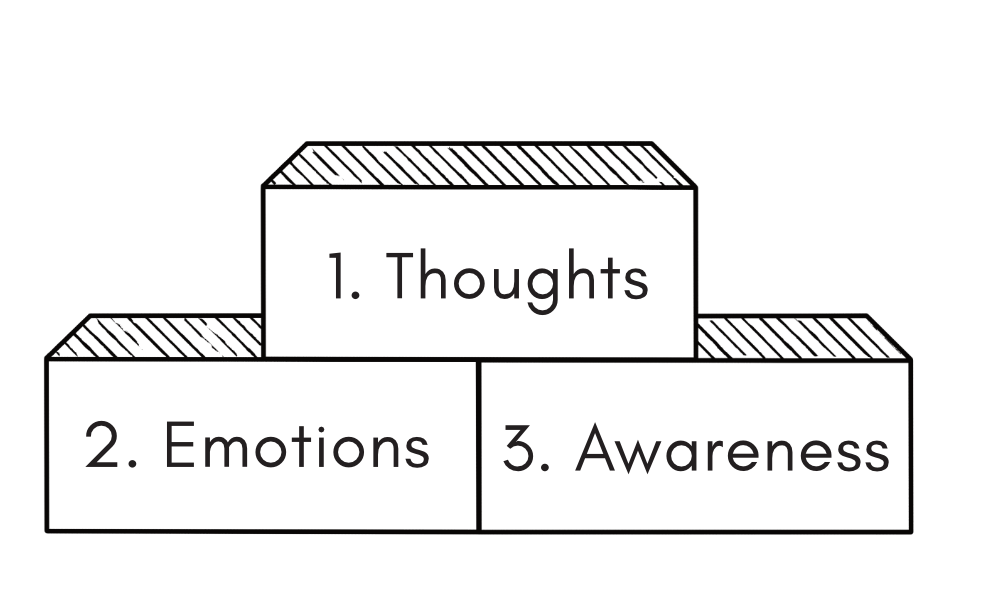

The 3 Building Blocks

It all begins with an idea.

First, let's learn about an important principle which is at the core of the Fount model. Based on this model, there are 3 building blocks that constitute our psychological existence: thoughts, emotions, and awareness. Although in principle we are all well familiar with these 3 building blocks, but you may be surprised to find that in practice, most of us can struggle to differentiate between them. And I’d like to suggest that learning to differentiate between them is at the core of successful clinical practice. Let's take a closer look at each.

1. Thoughts

Let's begin with the first building block: thoughts or cognitive elements. Picture this - thoughts are like an internal conversation, a cinema screen in our minds, or even a sports commentator providing commentary on everything as we go about our day. They are formed from words, images, or ideas. From analyzing and judging things to planning and coming up with new ideas, thoughts are the general activities of the mind. And when I say the word ‘activity’, I need to highlight that word. Thoughts are about doing. They are the act of using logic, rationality, and imagination, naming, comparing, categorising, judging and so on. I would like to invite you to take a moment to watch your thoughts, or listen to your internal dialogue. It may help to close your eyes, bring your attention inward and pay attention. See if you can get to know your own thoughts for a minute. I suggest you pause the audio and try it now.

2. Emotions

Now, let's move on to the second building block: emotions. Unlike thoughts, emotions are not based on language. Instead, they are pure experiences, much like the taste of an apple - something that's hard to put into words. You could try to describe how an apple tastes to someone who’s never had an apple before, but they could never quite understand the taste of an apple until they’ve tried it for themselves, right? Because experiences are not language based. They need to be felt and experienced. Language can’t communicate them effectively.

We often feel emotions somewhere in our bodies, like a racing heart or trembling knees when scared, butterflies in the belly when anxious or excited, heaviness in the head or eyes when feeling down, or the heat of anger. At times emotions are still. At other times they are restless and chaotic, moving, pulsating, or appearing and disappearing. We don’t always know that we are feeling an emotion, or what kind of emotion we are feeling. At times, the emotion can feel purely physical and somatic.

Try to take note of your emotions for a minute. It may help to close your eyes. See if you can scan your body for a minute and notice any emotions that you may be feeling right now. You may like to pause the audio to give yourself as much time as you need.

Another feature of emotions is that they can be pleasant or unpleasant, but thoughts, on their own, do not carry such inherent qualities. For example, you can have a thought ‘I’m not good at playing the piano’ without any emotional attachment. It’s just a thought, an understanding that I’m not good at playing the piano. But the same thought could have an emotional attachment for someone else. They could feel sad or upset about not being able to play the piano well. In that case, the thought and the emotion may happen concurrently, but still they can be seen as qualitatively different. The Fount model emphasizes the importance of recognizing the fusion of thoughts and emotions and yet recognise their qualitative distinction.

3. Awareness

Lastly, let's explore the third building block: awareness. Often confused with thinking or emotions, awareness is entirely different. Similar to emotions, awareness is not composed of words and sentences. It is the simple act of noticing things, like looking, listening, tasting, smelling, and feeling.

As humans, we tend to quickly start thinking about whatever we notice. Imagine seeing a pink flower; initially, you simply notice its shape, color, and smell. But then your thoughts may soon follow, like, ‘I like this flower, but I like red flowers better,’ or ‘I wish my partner would surprise me with flowers.’ Again, although thoughts and emotions may arise soon after noticing, they are qualitatively different and it is helpful to be able to differentiate between them. The act of noticing and becoming aware is also what we call mindfulness.

Let’s do an exercise to help with noticing awareness. The following section is an excerpt from my book Mind Wellbeing.

“Pick up an object and hold it in your hand. It can be a pen, a book, a spoon, a flower etc. First spend some time thinking about this object. Notice that your thoughts are made up of words. They may look like this:

'This is a nice looking pen. I like the shape. But it doesn't write so well. My other pen writes better. I wonder where it was made. Is it cheap or expensive? I should write with the other one though, it's nicer to write with.' And so on.

Notice your thoughts as they take place.

Now spend a bit of time just looking at the object. No thoughts. No commentary. Just look at it. And feel how it feels in your hand. Maybe smell it. Notice the object, with all its little details, with all of your attention.

This is called awareness, or the act of mindfulness.”

Therapeutic Implications of the Building Blocks

It all begins with an idea.

First, let's take a look at the relationship between mental health and thoughts. As mental health declines, a combination of changes occurs to our thought patterns. Research has shown that many mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression, lead to an increase in the frequency and intensity of thoughts. These conditions can result in heightened rumination and overthinking, leading to a continuous stream of repetitive and intrusive thoughts. During manic episodes in Bipolar Disorder, thought activity can significantly escalate, with racing thoughts and difficulty in focusing on one idea. Many conditions, such as schizophrenia or other psychosis can result in disorganized and fragmented thinking.

Next, let's look at what changes we could expect to our emotions as mental health declines. When experiencing mental health challenges, emotions tend to intensify. We know that individuals facing mental health challenges often experience heightened emotional responses to various situations. Emotions like anxiety, sadness, or anger, may become more frequent and intense, making it challenging to regulate emotions effectively. Feelings of overwhelm, vulnerability, and emotional exhaustion are common as individuals navigate the complexities of mental health difficulties.

While the rate and intensity of thoughts and emotions can increase during mental health crisis, the impact of mental illness on mindful awareness can be the reverse. As mental health declines, our ability to engage in mindful awareness may reduce or diminish. This is particularly evident in individuals with severe mental health conditions, as these individuals may have very little awareness of their surroundings or ability to be rooted in the present moment. A decrease in mindful awareness might lead to a higher prevalence of autopilot thinking, where our minds habitually wander, dwelling on past regrets or future anxieties, without truly being present in the moment.

The following graph is a rough illustrative demonstration of the relationship between mental health conditions and the 3 building blocks:

In contrast, a mentally healthy individual can enjoy periods of rest from cognitive activities through increased mindfulness and emotional calm. Their existing thoughts are more likely to be balanced with mindful awareness, reducing the tendency for autopilot thinking, rumination, or worry. As a result, their emotions become interspersed with periods of calmness, where they can experience a sense of emotional balance and equanimity.

In he following slides, we'll explore strategies and practices that can assist clients on the level of each of these building blocks.

Addressing the Building Blocks in Therapy

It all begins with an idea.

During therapy, it's essential to address these 3 building blocks using distinct therapeutic tools and with a level of discernment and purposefulness. Addressing each area requires a thoughtful and tailored approach. Below are the specific tools and techniques that I recommend for addressing each of these areas:

Thoughts: To modify thoughts effectively, we employ cognitive reappraisal. In my practice, I like to combine traditional cognitive reappraisal techniques with imagery work.

Emotions: When working with emotions, body-oriented therapies have shown great promise. Specifically, I find that emotion or interoceptive exposure are ground breaking techniques that deserve a lot of attention in the clinical field.

Awareness: Using mindfulness strategies, including present-moment focus, can assist us in cultivating awareness. I often find that as thoughts and emotions become better managed, mindful awareness naturally increases. At other times, I need to purposefully incorporate mindfulness strategies in the therapeutic process.

In the following slides, we will explore each of these strategies in more detail, discussing their benefits and practical applications.

Thoughts: Cognitive Restructuring and Reappraisal

It all begins with an idea.

Although, as therapists, we come from various therapeutic backgrounds and use different methods and modalities in our work, it's safe to say that we all use cognitive restructuring or reappraisal to one degree or another. As you are no doubt aware, cognitive restructuring or reappraisal are the act of reevaluating and reconsidering one's thoughts, beliefs, and perspectives. These techniques are a fundamental aspect of most therapeutic approaches and whether we realise it or not, most of us incorporate some form of it, in our therapy sessions.

Delving into all the nitty-gritties of how to apply cognitive restructuring or reappraisal is outside the scope of this course, but we will discuss a few key aspects related to its use and explore how we could use it most effectively.

Substituting vs re-evaluating

When it comes to methods of reappraisal, there are two main schools of thought:

Traditional Cognitive Restructuring: This approach involves challenging "thinking errors" by replacing them with more rational or accurate thoughts. The focus is on substituting or replacing thoughts with healthier alternatives.

Evidence-Based Cognitive Reappraisal: This approach places emphasis on evaluating thoughts against available evidence and considering alternative perspectives. Therapists help clients develop critical thinking skills by examining the accuracy and validity of their thoughts. Instead of solely prescribing alternative thoughts, this approach encourages clients to engage in a process of evidence-based evaluation. Furthermore, instead of replacing or substituting thoughts, clients organically arrive at alternative conclusions through this process of re-evaluation.

Traditional cognitive restructuring techniques have faced certain criticisms over time. Some of these criticisms include:

Superficial Treatment: Critics argue that traditional cognitive restructuring techniques can focus solely on changing surface-level thoughts without addressing deeper underlying beliefs or core schemas that contribute to cognitive distortions.

Overemphasis on Positive Thinking: This is one that I personally feel quite passionate about. Research consistently highlights that experiential avoidance, which is the act of suppressing or avoiding distressing thoughts, emotions, or sensations, can lead to increased psychological distress, reduced well-being, and hinder personal growth. Studies underscore the importance of facing and accepting challenging experiences, as avoidance tends to prolong emotional suffering and contribute to the persistence of mental health difficulties. Naturally, this means that we need to approach with caution any therapeutic approach that pushes us away from our real feelings and encourages avoidance. Critics suggest that the emphasis on replacing negative thoughts with positive ones might oversimplify complex emotional experiences and potentially lead to a pressure to always think positively. This approach could downplay the importance of fully experiencing and validating one's emotions. The term 'toxic positivity' has emerged to describe this phenomenon, shedding light on the potential drawbacks of excessive emphasis on positivity.

Focus on Control: Encouraging excessive control over one's thoughts might inadvertently discourage the valuable practice of accepting thoughts as they naturally arise. It could steer individuals towards avoidance strategies, encouraging them to distance themselves from uncomfortable or distressing thoughts rather than developing a healthy relationship with them.

Critics of traditional cognitive restructuring have pointed out that an overemphasis on thought control may inadvertently lead to avoidance of uncomfortable or distressing thoughts. This avoidance can hinder the process of fully engaging with one's thoughts and emotions, which is essential for meaningful personal growth and psychological well-being. Instead, approaches that focus on acknowledging, accepting, and mindfully observing thoughts without immediate attempts to control them have gained prominence as more holistic and effective strategies in therapeutic practices.

In addition, some critics highlight that the emphasis on control over thoughts might inadvertently reinforce a sense of inadequacy or self-blame when individuals struggle to completely control their cognitive processes. My personal observation is that these approaches can contribute to mental exhaustion over time, as people feel a constant need to wrestle with, control, shape or replace negative thoughts.

A seasoned therapist takes a more nuanced and thoughtful approach to cognitive restructuring. Rather than simply prescribing alternative thoughts, a skilled therapist guides clients through a process of evidence evaluation. When we encourage clients to critically assess their thoughts against any available evidence, clients arrive at more helpful and realistic conclusions on their own. This approach promotes deeper insight and equips clients with tools to identify, evaluate and modify their thought patterns independently.

I should clarify that a skilled and experienced therapist can apply Traditional Cognitive Restructuring in a manner that involves guiding clients to evaluate their thoughts against evidence and encouraging deeper exploration, similar to the principles of Evidence-Based Cognitive Reappraisal. The main point of differentiation is that Evidence-Based Cognitive Reappraisal places a particular emphasis on evidence evaluation, which is not always as explicitly highlighted in all applications of Traditional Cognitive Restructuring.

Present and Past Thoughts

While we might not always realise it, the use of cognitive reappraisal or restructuring extends beyond our current thoughts. This transformative process is harnessed by various therapeutic approaches, such as CBT, Schema Therapy, Narrative Therapy, EMDR, Internal Family Systems (IFS) Therapy, Hypnotherapy, and Gestalt Therapy, often integrating imagery work to facilitate healing around past memories and traumas.

And here are a couple of practical examples to illustrate these concepts:

Example 1: Rewriting Childhood Memories

When practicing cognitive restructuring, imagery becomes a potent tool that assists with the exploration of our past experiences. Imagine a client who, as a child, experienced a significant event that left a lasting negative impression. Using imagery, the client is guided to revisit this memory, engaging their inner child. Through compassionate dialogue and reframing, the client's adult self can provide understanding, reassurance, and new interpretations. This process not only reshapes the memory's emotional charge but also fosters a sense of healing and integration.

Example 2: Addressing Traumatic Experiences

Various therapeutic modalities, including EMDR, trauma-focused CBT, and narrative therapy, harness the potential of imagery work to address deeply rooted traumas. Narrative therapy, for instance, encourages individuals to reconstruct and retell their life stories, often incorporating imagery to create a new narrative that empowers them and reframes their experiences. Similarly, in EMDR and trauma-focused CBT, imagery work plays a crucial role in facilitating cognitive shifts and emotional healing by allowing clients to view their traumas from different angles.

Imagination as a Source of Healing and Harm

Imagination can be seen as a double-edged sword, capable of both psychological harm and benefit. Often, we may not fully realise the immense power that our imagination holds in shaping our emotional experiences and psychological landscape. So, let's take a closer look at this.

Imagination and Psychological Harm: In our formative years, imagination plays a significant role in shaping our beliefs about ourselves and the world. According to Karen Horney's theory, “the idealised self” is born when a child uses their imagination to create a perfect idea of who they should be. However, this imagination can turn into an unrealistic expectation, leading to feelings of inadequacy, anxiety, and self-criticism later in life. Such maladaptive use of imagination can create a host of future issues that impact mental well-being.

Additionally, scholarly research has shed light on the potential risks of excessive or maladaptive fantasising, which involves the creation of intricate mental scenarios often for the purpose of escaping reality or wishful thinking. Studies have indicated that chronic fantasising may correlate with increased levels of anxiety, decreased psychological well-being, and difficulty in managing negative emotions (Smith et al., 2018; Soffer-Dudek, 2018). This highlights the delicate balance between the creative potential of imagination and its potential to contribute to psychological harm.

Positive Use of Imagination in Therapy: On the other hand, when we purposefully engage in imagination during therapy, we unlock its potential as a powerful tool for positive change. Imagery work allows us to tap into the creative depths of the mind, encouraging clients to explore alternative perspectives and cultivate more balanced and rational thoughts.

While there are many techniques for the use of imagination in therapy, our main goal is usually this: to travel with the client to a specific time in the past or future and then to help them see events or their understanding of the events in a new light. A good practice is to inform the client that although we can't change the past, that what's done is done, through this exercise can change how those events affect them now. In other words, by imagining the past differently, we might feel different emotions, and that can extend to how we feel today.

Stay tuned as we have some practical examples and case studies lined up in the next section, to help you develop a real grasp of how to apply cognitive appraisal and imagery exercises for various mental health conditions.

Cognitive Reappraisal and Self Image

It all begins with an idea.

In the next few pages we will circle back to our old friend, Maslow's hierarchy of needs and explore how we can utilise cognitive reappraisal strategies for the treatment of deficits in each tier of the triangle. First, let’s take a look at the self image tier of the triangle:

If you've identified that the Self Image and self-esteem tier of the hierarchy of needs is your client's primary concern, there are two critical areas that require attention:

1. Current Thought Errors:

The types of thought errors that you are likely to encounter with a client experiencing self-image issues revolve around comparisons between oneself and others, manifesting in the following thoughts or core belief patterns:

I am LESS than others due to one or several weaknesses, failures or deficits. For example, I am less than others because I don't know how to suceed in life, I don't know how to fit in, I am physically unattractive, I am financially or educationally behind, I am weak or emotional and so on.

Other people view me as less favourable, less significant, less desirable, less interesting, less admirable than others due to one or several weaknesses, failures or deficits.

I am MORE than others due to one or several strengths, features or abilities. For example, I am more worthy, more exceptional, more unique, more admirable, more virtuous and so on.

Or a combination of these.

Please note: we are not talking about a client's constructive assessment of their abilities, stenghts or weaknesses. In fact, the ability to be self critical and be able to rationally assess one's challenges along with strenghts is indicative of a healthy self-image. The type of thoughts and core beliefs that we are referring to here are excessively negative, emotion ridden (e.g. feelings of inferiority, shame, anger, self blame, competetiveness, over excitement or euphoria associated with accessive pride) often accompanied by thinking errors such as emotional reasoning, catasrophising, over-generalising, magnification/minimisation etc.

The process of therapy involves carefully examining these thoughts with clients and exploring their accuracy against evidence, as the client is ready to engage in such exploration.

One more point to remember is, in keeping with the principles of emotion regulation and to avoid inadvertently encouraging experiential avoidance and toxic positivity, we also need to inform clients that once their thoughts are shifted, their emotions may or may not match their thoughts yet. This means that they could have a more rational and balanced view towards the situation, but underneath those thoughts, they may still feel shame, embarrassment, a sense of failure, inferiority, or a sense of defeat and helplessness. In other words, the process of cognitive shift isn't a magical wand that immediately erases underlying emotions. In fact, it's entirely normal for the emotions to lag behind the cognitive shifts. The purpose of cognitive reappraisal is not to diminish these emotions. Other techniques that we will explore in future sections can assist with alleviating emotions. So clients can stay true to their existing emotions, accept these emotions, and not try to fight or control them. While simultaneously, they can review their thoughts and adjust them to a more rational view.

Let's look at an example to illustrate these principles in action. Imagine working with Alex, a capable individual who tends to downplays his achievements in his career or personal life. Your conversation might unfold like this:

Therapist: Alex, you've mentioned feeling hesitant about your recent accomplishment. Can you share more about that?

Alex: Well, I kind of feel like I got lucky with it. Maybe it wasn't a big deal. Or maybe I'm a fraud and people will soon see that I'm really not very capable.

Therapist: Can you remember another time when you tackled a similar challenge and received positive feedback from your colleagues?

Alex gives several examples of his past accomplishments.

Therapist: That's a great. It seems like your skills often do come through when you face various challenges. Could it be that your recent accomplishment wasn’t just luck? What if we looked at your recent achievement through that lens?

Alex: I guess I could see it as a reflection of my skills.

If, as seen in this example, our client shows a willingness to embrace new perspectives and adjust their views with a level of ease, focusing on the present moment could be enough to achieve our goals. However, if the client's fundamental convictions seem to be deeply ingrained and resistant to change, or if we notice that the client consistently disregards current realities and evidence, it may be helpful to delve into client's past memories, particularly those from his middle childhood.

2. Past Memories:

An essential first step is to determine key events that may have contributed to an unhealthy self-image. As we learned in the previous module, by working together with your client to delve into their history, you can pinpoint specific moments that hold emotional weight. For instance, let's go back to the case of Alex. Through exploring his history, you may come to realise that he first experienced feelings of inadequacy in primary school (middle childhood) due to a yet to be diagnosed case of dyslexia, which made him feel like he wasn't adequate, as well as a schoolyard bully that made him feel like he didn't fit in with his peers.

Therapist: Can we take a minute and explore something? It's a technique called imagery work. I'll guide you to use your imagination to travel back in time to specific moments from your past and then, by imagining things a bit differently, you can gain new insights and perspectives. Of course the past is the past and we can't really change it, but through imagining it differently, we can change the way that we are impacted by it today. Close your eyes if you're comfortable, and imagine you're traveling back in time to your childhood. Can you remember a time when your carefree childhood feelings were replaced by the ideas of self doubt and feeling not good enough? Do you remember any memory like that?

Alex: I remember struggling a lot with reading and writing at school. All the other kids seemed to get it, but I kept struggling. I had dyslexia, and it made me feel like I wasn't as smart as the other kids in my class.

Therapist: I'm sorry to hear you experienced that. Can we try something now? Imagine if your adult self, or some else you trust, was to step into the story and support your younger self through this experience? What do you think he needed to hear? What would you like to do for him?

Alex: I'm not sure. Maybe somehow making his dyslexia disappear?

[Note: Often clients opt for imagery solutions that involve changing external circumstances in their past. The issue with this type of strategy is that, in reality the client has still experienced what they have experienced, and the imagery work has not addressed the need for the experience to be reframed. Hence, usually, the best use of these imagery exercises is to assist the client to still go through the experience, but try to make sense of the experience or reshape their thoughts around it.]

Therapist: We can try that. But in reality, this child will still have a memory of what it felt like to have dyslexia and feel inadequate in class. So maybe instead of making the dyslexia disappear, we could help him understand that his dyslexia doesn't make him less worthy than other kids. We could tell him that his dyslexia is just a specific challenge in a specific area, and that all people will experience their own challenges in life. Having challenges doesn't make you less worthy. You could practice the things that are a little hard, like your spelling, and eventually become better at them. Or you could shine even brighter in the things that you're already good at, like sports or science. It's all about having fun and learning new things! Every kid's journey will be different, so you don't have to compare yourself to the other kids around you.

[Note: The purpose of this dialogue with Alex is partly to convince adult Alex why his child self wasn't inferior than his classmates. Once he is convinced of this, he can use imagery to convince the child in his imagination as well. For some clients this step may take a bit more time as their self worth is so deeply scarred, that they can’t even accept that as a child they were worthy or deserved better. For such clients, you may need to focus on broader cognitive restructuring aimed at improving their self work a bit longer before they are ready to delve into childhood imagery work. A good strategy would be to try to detect any maladaptive core beliefs that may cause them to have such poor self image.]

Alex: I guess I can see your point. The dyslexia was just a challenge. I didn't need to form such a negative self image around it.

Therapist: Exactly, can you imagine if someone had told little Alex about all of this back then? Can you close your eyes again and talk to him about it?

Alex: I would tell myself that dyslexia doesn't define my worth. I'd say that I have strengths and abilities that go beyond just reading and writing.

Therapist: That's great! How does your younger self feel after hearing these words?

Alex: He feels a bit lighter, like there's more to him than just his struggles. But he's still worried about the schoolyard bully. He still feels like there is something wrong with him if the bully picks on him.

Therapist: Shall we use the same technique to support him through the bullying as well? What did the bully say or do that was hurtful?

Alex: He kept telling me that I was annoying and no one wanted to play with me.

Therapist: And you believed him?

Alex: I'm not sure. I mean, there were times when I was alone during breaks and no one was playing with me. So yes, I did believe him.

Therapist: What about at other times? Were there times when things were different?

Alex: I do remember playing and having fun with the other kids at times.

Therapist: So what do you think caused you to fit in one day, and not fit in another day?

Alex: I remember standing on the side of the schoolyard and keeping to myself a lot. Not really mixing with the other kids. I was too shy or anxious to mix with them.

Therapist: Do you remember why you were shy or anxious?

Alex: Because I kept remembering the words of the bully kid. I thought I was annoying and no one wanted to play with me. So I pulled myself away.

Therapist: And while you were pulling yourself away, naturally the other kids left you alone. And in your mind, that must have confirmed what the bully was telling you.

Alex: Exactly. It kept firming up the belief that no kid wanted to play with me.

Therapist: Sadly bullies often tell us that there's something wrong with us and it's understandable that you believed what the bully was telling you. But it's good to remember that the purpose of a bully is to make you feel bad about yourself. If their purpose was to tell you the truth, they could have done it in more gentle ways. So it's wise to not believe all the negative things that a bully tells you about yourself. Do you think we could tell the younger you to not believe the bully?

Alex: Yes, he now realises that if he just went back into the playground, other kids would play with him. He feels like he fits in.

The Domino Effect of Memories

One thing to keep in mind here is a principle referred to as the cascading effect or the domino effect of memories. As we know, early memories act as a foundation for interpreting later events in life. During the process of therapy, if we change a client’s perception of an earlier memory, a cascading shift can ripple through time, influencing how they perceive subsequent experiences. In Alex's case, for example, the core belief "I'm not good enough and I don't fit in" was maintained as part of his identity and once he hit adolescence, a combination of challenges like puberty, increased peer pressures and highschool bullying caused this belief to exacerbate even more. Later, adulthood experiences such as employment challenges or searching for a partner further cemented this belief in. As you can imagine, once the belief “I’m not good enough” or “I don’t fit in” is there, life would create a myriad of scenarios to confirm this existing belief.

Once therapy had helped Alex develop a new understanding of his middle childhood experiences, not only was his self-perception in the present moment transformed, but a ripple effect was initiated whereby he began reframing his memories of adolescence and adulthood too. At times you may find that this ripple effect happens automatically, as your client starts pondering all the subsequent memories and developing a new view of them. At other times, you may need to manually help your client apply their new understanding to the subsequent events of their life.

In contrast, you may find that if you first attempted to shift Alex’s view of his adolescence and adulthood, his views would be more resistant to change as he would still remember the events of his adolescence and adulthood through the lens of a child who was less than his peers as he couldn’t spell or fit in. That earlier belief needed to have been shifted first. After addressing the earlier memories, the intense emotional charge connected to later events, such as high school difficulties, also began to diminish. Transforming the core, foundational memories can gradually reshape the entire narrative of Alex’s sense of self-worth.

Another way to view this principle is that early memories can serve as templates or reference points for how we interpret and respond to later life events. Thus, modifying our perspective on these foundational memories can potentially have a positive influence on how we view and process more recent experiences.

So from a practical standpoint, we are suggesting that a rule of thumb is to commence the exploration with the event that occurred at the youngest age and progressively work through to more recent memories. However, therapists may encounter situations where clients display resistance to revisiting earlier memories and instead prefer to focus on later-life events. This inclination can be attributed to the escalating intensity of negative emotions as clients navigate through life's challenges. For instance, a memory from age 7 might seem less emotionally charged than one from age 18, as years of challenging experiences would have eroded client’s self-worth even further. Clients often express that while the origin of their self-esteem issues dates back to middle childhood, these issues didn't gain prominence until later stages of life. This is where psychoeducation comes into play. It's crucial for therapists to help clients comprehend the significance of revisiting earlier memories, even if the associated emotions appear less intense, as it lays the groundwork for untangling the web of self-perception. Below is an analogy that I like to provide to clients about this principle, to help them understand the logic:

"Just like a big tree starts as a small seed, our feelings about ourselves also begin when we are very young. Even though those early feelings might not seem as big as the ones we have now, they are like the roots that grow into the big tree. To understand the big tree, we need to look at how it started as a little seed and grew. In the same way, to understand how you feel about yourself today, we need to go back and see how it all began when you were younger."

Cognitive Reappraisal and Attachment

It all begins with an idea.

In this section we will explore how cognitive reappraisal techniques can be applied if you have identified that the attachment and connection tier of the hierarchy of needs is your client's primary concern.

The types of thought errors that you are likely to encounter with a client experiencing attachment related issues revolve around the belief that they are not loved or cared for by others, hyper-sensitivity to abandonment, maladaptive beliefs around others being trustworthy or well-intentioned and a tendency to feel alone. Clients justify these beliefs by adhering to evidence from both past and present experiences.

1. Past Memories:

Childhood memories which create the belief that the child is not loved or cared for by adult caregivers are the primary foundation for attachment-related challenges. Attachment theory, initially focused on infancy, extends its influence beyond that period, encompassing toddlerhood and early childhood. While the foundations of attachment are primarily formed during infancy, they continue to evolve and interact with a child's growing cognitive and emotional capacities beyond that age.

In my experience, when engaging in imagery work with clients who have encountered environments marked by inadequate attachment, a common pattern emerges: these individuals frequently recollect their earliest memories of abandonment, feeling alone or not cared for, from the age group of 3 to 6 years. This observation aligns well with the principle of cascading memories, as well as Erikson's psychosocial theory. Erikson's theory highlights the significance of the 'Initiative vs. Guilt' stage during these formative years, where children develop a sense of control and initiative over their environment. Poor attachment experiences during this phase can leave a lasting impact on a child's sense of security and control. Additionally, memories from this stage hold a unique blend of accessibility and richness due to the emergence of language skills, cognitive abilities, and moral awareness. This combination of factors makes memories from this time particularly poignant for clients. As a result, addressing memories within this age range through cognitive reappraisal allows for targeted and effective interventions, enhancing the potential for meaningful transformation. By revisiting memories from this age range and applying cognitive reappraisal techniques, we can help clients reframe early experiences and foster more secure attachment patterns that can cascade through a client's life. Let’s take a look at an imagery exercise to illustrate these principles in action.

Therapist: It sounds like you've been through a lot during your early years. I've noticed that there's a recurring theme of loneliness and not feeling cared for whenever we have talked about your past. Would you be open to exploring these feelings a bit today through an imagery exercise?

Sarah: Yes, sure, let's try it.

Therapist: Let's start by focusing on a particular memory. What's the earliest memory that stands out to you from your childhood?

Sarah: There's this memory from when I was around 5 years old. My mom was always distant, lost in her own world, and my dad wasn't in the picture. My siblings were dealing with their own stuff, and I often felt like a burden. I remember wanting to play with them or talk to them, but they would push me away and tell me to leave them alone. It felt like my presence was a burden to everyone. I was just not lovable.

Therapist: Now, imagine that you, the present-day grown-up Sarah, could travel to the past and be with the child Sarah as her mum is mentally absent and she's experiencing being pushed away by her siblings. But you're not there to push her away; you're there to show her the love and care she needed. Can you do that?

Sarah: No, I can't do it. I'm not sure why. It's like there's a wall between me and that little girl.

Therapist: Look deep within your heart. How do you feel towards that child? Do you feel love and compassion towards her?

Sarah: No, I feel angry towards her. I feel horrible saying this, because I normally love children. But I can't feel love for this child. I have such negative feelings towards her. I feel like if she was a bit less pathetic, her mum and siblings wouldn't push her away.

[Please note: during imagery work, when you come across clients who, like Sarah, struggle to extend love and compassion towards their younger selves, this should be considered as a sign of the severity of their self worth and attachment issues. With these clients, your first goal becomes to help them grow compassion towards their child self.]

Therapist: Sarah, please don't blame yourself for struggling to love that child. Your struggle to connect with your younger self is completely understandable, given the experiences you've had. Growing up, you didn't receive the modeling from the adults around you that this child version of yourself was deserving of love and care. This is exactly why we're engaging in this exercise – to bring healing and change to those deep-rooted beliefs. You could say that as you gradually grow love and compassion towards that child, you will also be growing love and compassion towards yourself. This may take some time, so don't feel like you have to achieve it overnight. And you're not doing this alone – I'm here to support you through it.

[Please note: It's common for clients to feel guilt when they struggle to love and care for their inner child. The purpose of the above statement from the therapist is to set the client's mind at ease that they are not judged and that they can let go of their guilt so that these thoughts could be explored freely.]

Sarah: Thank you. It's good to hear that.

Therapist: Do you feel ready to continue?

Sarah: Yes, let's continue.

Therapist: You know, it's quite common for children to view adults as having everything figured out, almost as if they're perfect. But the truth is, adults have their own struggles and challenges too. Your mom might have been dealing with her own issues, maybe mental health concerns, that made it difficult for her to be as present as she should have been. And your siblings, they were also navigating their own difficulties. It's possible that they never learned how to be fully present and caring because of the family's difficult circumstances. The family was struggling as a whole. You interpreted their actions as a reflection of your own worth, but that's not accurate. The 5-year-old Sarah wasn't responsible for the actions or behaviors of the adults and siblings around her. You were just a child, seeking the love, care, and validation that any child needs.

I wanted to also tell you about a cycle that can form where the more a child feels pushed away, the more desperate they become to receive love and attention. As a result the child may start to act either overly reserved or overly clingy. The child's clingy or reserved behavior can then lead to the adult caregivers responding negatively, causing the child to feel even more unloved and rejected. Unfortunately this is a common cycle that can happen with neglected children. It is a possibility that these dynamics impacted you as a child as well.

So with all of this in mind, can you logically agree that there was nothing inherently wrong with little Sarah? That she was simply a child in a challenging environment, doing her best to navigate the circumstances around her?

Even if you find it challenging to emotionally love little Sarah right now, could you at least acknowledge, from a rational perspective, that she did deserve love and care, just like any other child?

Sarah: You have given me so much to think about. Logically, I can see your point. I wasn't bad or broken. I was just a normal child within an unhealthy environment.

Therapist: And how do you feel now, with all this new perspective?

Sarah: I feel sad for her. I mean, I still struggle to fully accept and love her. But I'm a bit more open to it. I feel like I'm not so angry with her anymore.

Therapist: That's a step in the right direction. It may take some time for your emotions to fully shift. That's totally okay. Emotions can take time to catch up with our thoughts and realisations.

2. Current Thought Errors:

When working with clients who are grappling with attachment issues, you'll often come across thought errors that revolve around their connections with others and the security they feel within relationships. These thought patterns might involve doubts about the authenticity and dependability of other people's care and affection for them. Or they may hold the belief that they are intrinsically unworthy of love and care.

The biggest "here and now" issue with this group of clients is a need for them to realise that although earlier in their life, their social connection issues came from outside sources (i.e. neglectful or abusive caregivers), their current struggles with relationships mostly stem from their own maladaptive beliefs, habits and behaviour. As a therapist hearing story after story where your client with attachment problems was treated terribly, ending up feeling abandoned, rejected or betrayed, you may start wondering: what is going on here? Is this person incredibly unlucky? How come they keep experiencing such a dark side of the society on a consistent basis? This line of questioning may continue for you until a point where you find yourself surprised that your own innocent behaviour was interpreted by your client as a sign of abandonment or abuse. Or where the client communicated with you in highly ineffective ways, leading to a myriads of misunderstandings within the therapeutic setting. This, usually, is the point where therapists stop and wonder: am I dealing with a personality disorder here??

The consistent patterns of abandonment, rejection and mistreatment experienced by clients with poor attachment are a result of three main mechamisms:

1) Scarring their realtionships through hyper-sensitivity and poor communication: Clients with attachment issues often grapple with poor emotion regulation, maladaptive coping strategies, and intense emotions like anger, clinginess and tendency to take offense easily. Moreover, they are often challenged with poor communication, an issues that likely stems from lacking positive communication models in their family of origin. These challenges can contribute to increased likelihood of experiencing rejection and abandonment by those around them due to frequent relationship breakdowns.

Cognitive reappraisal: One of the goals of the therapeutic journey is to explore with the client these problematic communication patterns with due sensitivity to their emotional landscape. Through cognitive reappraisal, the therapist delicately guides the client to a deeper understanding that certain communication patterns, might inadvertently distance others or harm their relationships. This realisation is not about making the client feel blamed or holding them accountable for their past actions; instead, it is to help them gain insight into the root causes of their relational challenges. If these therapeutic processes are done with due sensitivity and care, clients often find relief and renewed hope in uncovering the origins of the patterns they have found perplexing their whole lives.

Balancing Care and Honesty, therapists must navigate the fine line between gentleness and transparency. If we manage to communicate with sensitivity and honesty, clients can find their renewed understanding liberating, as it fosters a sense of agency and the potential for healthier connections.

An important element of this is educating clients with attachment problems about healthier communication styles. The exploration of healthier communication strategies is a large topic that extends beyond the scope of this module. We will be exploring communication strategies in upcoming modules or you may like to refer to the chapters on communication within the Mind Wellbeing Workbook. These resources provide practical tools to help clients with attachment issues cultivate and sustain healthier communication habits.

2) Not perceiving or detecting genuine love/care: Individuals with attachment issues often struggle to perceive genuine love and care when they receive these. The idea that individuals with attachment issues might struggle to perceive or fully accept genuine love and care is well-established in the literature on attachment theory. This concept ties into their tendency to interpret situations through the lens of their past experiences and attachment patterns. People with attachment difficulties might have developed defensive mechanisms that make it hard for them to trust or believe in positive interactions. As a result, they might be more attuned to cues of rejection or mistrust and they may find it challenging to embrace positive feelings or connections. For example, when interacting with others, they may dismiss or not notice any signs that the other person cares for them or wants their company, but only notice the times when the other person is preoccupied with other things or fails to respond favorably.

3) Attraction to Abusive or Uncaring Partners: An additional element is that individuals with attachment issues often do become vulnerable to real abuse or mistreatment. This is due to the fact that they tend to get attracted to abusive or uncaring relationships, while rejecting genuinely kind or caring people. This further increases the likelihood of broken relationships or hurt and a reinforcement of their beliefs in relationships being insecure.

The phenomenon of individuals with attachment issues being attracted to abusive or uncaring partners is well-documented within psychology and relationship research. This pattern likely stems from the fact that these individuals are attracted to relationships that feel familiar and "normal" as they replicate the unhealthy dynamics of their early attachment experiences. Moreover, relationships with partners who treat them poorly might validate their negative beliefs about themselves, as they may feel they deserve such treatment.

So, here we can observe a paradoxical situation where people with attachment problems often find it easier to see love and care in abusive or uncaring people rather than in those who genuinely care about them. It's important to note that these patterns do not imply that individuals with attachment issues intentionally seek out harm. Rather, it often reflects deeply ingrained emotional patterns and a lack of healthy relationship models.

Cognitive reappraisal: An important task for cognitive reappraisal is to help these clients re-evaluate their relationships and their inner "detectors", so that they can understand:

a) which instances of relationship breakdown were due to their own hypersensitivity and poor communication;

b) which instances were due to not noticing or detecting genuine love; and

c) which instances were due to them simply choosing an uncaring or abusive partner.

A task of therapy, then, is to go through a journey of discovery with these clients, to assist them to find these distinctions.

Understanding the Paradox

The phenomenon of perceiving care in abusive or uncaring individuals while struggling to recognise it in genuinely kind ones is rooted in a complex interplay of psychological factors. Below are a few factors explored in the literature which may help us understand this perplexing dynamic, along with suggested intervention strategies using cognitive appraisal:

1. Attachment Blueprint: As we explored earlier, early attachment experiences serve as the foundation for understanding relationships throughout life, and a blueprint for how relationships should look like. Their early attachment experiences might have been characterised by inconsistency, neglect, or even abuse. These negative experiences, while painful, become ingrained in their understanding of relationships. As a result, they may be more comfortable or accustomed to relationships that mirror their past.

Cognitive reappraisal: When therapists observe these tendencies in their clients, it presents an opportunity to bring this pattern to the client's attention. By gently exploring their past attachment experiences and their influence on present relationship choices, therapists can help clients assess and challenge these deeply ingrained patterns. This process can shed light on the origins of their preferences and offer them the chance to redefine healthy relationship dynamics.

2. Low Self-Worth: Deep-seated feelings of unworthiness often plague individuals with attachment problems. As a result, they might struggle to believe that someone genuinely caring and kind would be interested in them. This disbelief can push them towards relationships that align with their self-perception and poor self image.

As we delve into the self worth aspect of attachment problems, it might be worth revisiting an idea that we previously discussed. You may remember that in Module 1 we suggested that while everyone with attachment issues tends to grapple with self-image problems, the inverse is not necessarily true. Meaning that it is possible for individuals with secure and healthy attachment styles to grapple with self image issues. Here it may be worth spending a bit of time exploring the distinctions and nuanced differences between the self worth/self image issues experienced by people with attachment problems and those without attachment problems. These differences can be summarised as follows:

Developmental Origins: Attachment-related self-image issues are likely onset earlier in life, influenced by the quality of attachment experienced with primary caregivers during infancy and childhood. Self-image issues not related to attachment, on the other hand, are likely to be created later in life. As explored in the previous module, they are frequently rooted in middle childhood experiences. At other times, they can be developed as a result of pressures or traumas experienced in adolescence or adulthood.

Depth and Scope of Impact: The depth of self-image and self-worth problems can differ significantly between individuals with attachment-related issues and those with self-image problems unrelated to attachment. For individuals with attachment problems, the self-worth issues can be deeply ingrained, pervasive and profound, often affecting their overall sense of identity and ability to form healthy relationships. On the other hand, self-image issues not tied to attachment may be more context-specific, potentially leading to fluctuating feelings of self-worth based on different situations. They are often centered around aspects of oneself that are not directly linked to their bonds with close connections and loved ones, but are related to external factors, societal influences, or personal attributes and capabilities.

Cognitive reappraisal: An effective approach to cognitive reappraisal here involves guiding the client to realise that the way their self-worth was defined within their family of origin is not a testament to their genuine worth as a person. Instead, the neglect, lack of empathy, or abuse that they experienced while growing up was a result of the dysfunction or stressful factors present within their family dynamics. As a result, these clients can begin developing an alternative explanation for the patterns of harsh criticism, disapproval, neglect or maltreatment they experienced, leading to a paradigm shift within their sense of self-worth.

3. Loss of Trust in Kindness: Perhaps the most powerful testament to the depth of these individuals' low self-worth and self-resentment is that, if attachment problems are severe enough, when the individual experiences genuine care and kindness, they are more inclined to perceive the caring person as flawed or insincere than to entertain the idea that they themselves might be deserving of such care. At times this tendency can result in them perceiving the caring person as having something inherently wrong with them. For example, they may believe that the kind person must be too lonely or unpopular to be able to find other company. Or they may perceive their kindness as a vulnerability or weakness. At other times, they may lose trust in the kind person, thinking that they must be insincere or manipulative. Within the therapeutic setting, they may believe that the therapist is only displaying kindness because they are getting paid for the sessions or because they are professionally obligated to do so. As you can imagine, navigating this tendency can be a significant challenge for the therapeutic alliance and this can account for much of the difficulties therapists face when trying to assist individuals with borderline personality or other personality disorders.

Cognitive reappraisal: Cultivating cognitive reappraisal around this issue entails several objectives aimed at dismantling the patterns of mistrust and negative labeling that individuals with attachment problems might exhibit:

Awareness Raising: As therapists, it's crucial to recognise when clients consistently label individuals who have shown them care or kindness in negative ways. By gently pinpointing this inclination, or bringing it to the client’s awareness, therapists can prompt clients to reflect on their own cognitive biases and how these biases might affect their perceptions of relationships.

Questioning Patterns: At times a deliberate line of inquiry may be necessary for the therapist to understand unhelpful patterns that may be impacting the client. When clients with attachment problems complain about consistent pattern of abuse, mistrust or hurt in their lives, therapists can quiz the client to see if there have been any exception to the rule, where the client experienced being treated well or with kindness? If so, how did the client perceive the individuals who treated them well? Did they trust or respect the kind individual? Did they enjoy their company? This line of inquiry can help detect any negativity that the client may have felt in relation with the kind or caring individuals that have crossed their path. The therapist can then help challenge any cognitive biases.

Exploring the Intentions of Others: People with attachment problems may face difficulties in accurately interpreting the intentions and behaviors of others due to potential challenges in emotional and social intelligence. Therapists can play a crucial role in gently probing clients' negative interpretations, helping them confront and reevaluate their perceptions. By highlighting instances where their assumptions might not align with the actual intentions of both caring and non-caring individuals, therapists guide clients to distinguish between past triggers and present reality. This process can empowers clients with a sense of confidence and control as they become more skilled at predicting the behavior of others.

Engaging in Therapeutic Dialogue: If the therapeutic relationship encounters moments of strain or disconnection due to clients’ tendency to replicate their attachment-related dynamics, such as miscommunication or mistrust, therapists can use these moments as opportunities for open and honest dialogue. Conversations centered on the client's feelings of doubt can be pivotal in building faith in the sincerity of the therapeutic connection. This open dialogue can potentially salvage the therapeutic bond during difficult moments and contribute to the healing process. These discussions also serve as a reflection of the therapist's commitment to maintaining a safe and open environment for communication, fostering a sense of trust that might have been absent in the client's earlier experiences.

Proactive Communication: It is beneficial to be proactive with clients with attachment issues, recognising the potential for them to distance themselves due to past dynamics, and establishing a foundation of open communication from the outset. This means that early on in the therapeutic relationship, it is beneficial to explicitly invite clients to voice their concerns and feelings of hurt, if these ever arise in the therapeutic relationship. By emphasising that the therapeutic relationship can be transparent and open around such matters, we can address these challenges head-on and mitigate potential misunderstandings. We can also demonstrate a departure from the negative relational patterns clients might have experienced in the past.

4. Repetition Compulsion: Some theories suggest that individuals unconsciously seek out relationships that replicate their past in an attempt to "rewrite" or heal their early attachment wounds. In the case of individuals with attachment problems, this often results in a tendency to engage in relationships with uncaring or abusive individuals in an emotionally driven attempt to finally receive the approval and affection of individuals who are reminiscent of their early caregivers. In some ways, individuals with attachment problems feel a compulsion towards receiving the care and affection of uncaring or callus people, as these are the types of individuals who made them feel unworthy in the first place. At times, I have found that this compulsion is so strong that even after they have become aware of its futility during the process of therapy, they still find it difficult to give up on this life long desire. In these cases, assisting clients to overcome this compulsive desire becomes a gradual and consistent goal of therapy for an extended period of time.

Cognitive reappraisal: The cognitive reappraisal process in this context aims to help clients recognise the futility of seeking care and affection from uncaring or callous individuals. An analogy that can be beneficial is to compare this situation to expecting apples from an orange tree. Just as you wouldn't get apples from an orange tree, seeking genuine care and affection from individuals who are emotionally disconnected and callous is unlikely to yield the desired results.

Psychoeducation about the mindset of uncaring and callous individuals can shed light on why their actions and behavior may not align with the client's expectations. It's important to emphasise that their lack of care is not a personal rejection but a reflection of their own emotional state and limitations at that given time. Clients can benefit from understanding that these individuals are often disconnected from their own emotions and empathy for various reasons, making it challenging for them to provide the care and affection the client seeks.

The goal of this cognitive reappraisal task is to help clients let go of the compulsion to seek care from those who cannot provide it and redirect their focus toward healthier, more fulfilling relationships. By understanding the limitations of these uncaring individuals, clients can work toward building relationships that genuinely meet their emotional needs and move beyond the repetition compulsion.

5. Need for Exaggerated Claims of Affection: Individuals with attachment problems can experience a heightened sensitivity to cues of rejection, and a reduced ability to perceive affection or praise. This tendency may mean that they require more pronounced or exaggerated claims of affection or praise to register in their awareness. Abusive or manipulative individuals can exploit this vulnerability by displaying intense and overstated claims of affection or praise as a means of control or manipulation. These exaggerated expressions can stand out more to those with attachment issues, and capture their attention more readily than the subtle yet genuine expressions of care found in healthier relationships.

Cognitive reappraisal: When therapists observe these tendencies in their clients, it presents an opportunity to bring this pattern to the client's attention.

6. Fear of Intimacy: Individuals with attachment issues might have an underlying fear of intimacy due to their early attachment experiences. Forming genuine connections can feel threatening to them, as it opens them up to the possibility of rejection and abandonment. As a result, they might gravitate toward relationships where intimacy is superficial, artificial, limited or absent.

Cognitive reappraisal: When therapists observe these tendencies in their clients, it presents an opportunity to bring this pattern to the client's attention.

7. Distraction Mechanism: Poor emotion regulation can result in distraction seeking behavior as individuals with attachment issues attempt to sooth their unresolved emotional pain and attachment wounds. Being with abusive or uncaring partners can often present much drama and chaos which can feel attractive to individuals with attachment issues, as it can momentarily divert their attention from emotional pain.

Cognitive reappraisal: When therapists observe these tendencies in their clients, it presents an opportunity to bring this pattern to the client's attention.

As you can imagine, the intricacies of treatment for people with attachment related issues are multilayered and there are many complexities. However, with a systematic approach that takes into consideration communication strategies and increased awareness of maladaptive attachment dynamics, we can increase the chances of success in therapeutic outcomes. A further element that is necessary in the treatment of these clients is the establishment of emotion regulation and mindfulness techniques. These will be covered in later sections.

Cognitive Reappraisal and Safety/Basic Needs

It all begins with an idea.

In this section we will delve into the lower two tiers of the hierarchy of needs, which share similarities with the challenges often associated with trauma. We'll explore the essential cognitive therapy steps required to address and heal these foundational aspects of well-being.

There are many exciting therapies emerging in the field of trauma. In this course, we won't extensively cover the field of trauma-informed therapies, given the wide range of approaches and ongoing developments. Instead, our focus will be on providing essential insights into our goals and methods when providing treatment to this client group, so that we can have a foundational understanding of our objectives and strategies.

When addressing trauma, we encounter a distinctive set of challenges that set it apart from other forms of psychological distress. Trauma often engages our primal fight or flight mechanisms and can have profound physiological and neurological effects. Therefore, navigating trauma therapy necessitates a comprehensive approach that considers the intricate interplay between mind and body. So before we delve into the cognitive reappraisal steps for these lower-tier needs, we'll need to touch upon several other elements of trauma therapy that must be holistically considered.

Some Thoughts on the Stabilisation Phase of Trauma Therapy

Stabilisation in the context of trauma therapy refers to the initial phase of treatment which focuses on enhancing the client's sense of safety, emotional regulation, and coping skills. It aims to prepare clients for the challenging work of processing traumatic memories and experiences. While the components of stabilisation can vary widely among different approaches or therapists, some typical elements of stabilization include:

Safety Planning: Collaboratively developing a safety plan to help the client feel safe about any overwhelming emotions that may arise during trauma processing. For example, you and your client could write down emotion processing strategies, emergency or support contacts, and other coping strategies to use if needed.

Grounding Techniques: Introducing grounding exercises that anchor clients in the present moment and prevent them from becoming overwhelmed by traumatic memories. Examples of grounding techniques include simple mindfulness strategies like focusing on the five senses, such as noticing or describing what they see, hear, touch, taste, or smell in their immediate environment. Additionally, clients can engage in rhythmic activities like deep breathing or tapping specific parts of their body to foster a sense of safety and connection to the here and now.

Relaxation techniques: Introducing deep breathing and relaxation exercises to help clients manage physiological arousal related to trauma triggers. For example, progressive muscle relaxation can be taught, where clients systematically tense and then release different muscle groups to promote physical relaxation. Additionally, diaphragmatic breathing techniques can be employed, encouraging slow, deep breaths to calm the nervous system and reduce anxiety associated with traumatic memories.

A common misconception is that effective treatment needs to follow an exact, step-by-step process, involving a stabilisation phase, followed by a trauma processing phase, and finally reintegration into daily living. The necessity of a stabilisation phase before trauma work has been a topic of debate within the field of trauma therapy. The concept of stabilisation often stems from models like Herman's phased approach for complex PTSD, suggesting that a stabilisation phase should happen before trauma processing. It's important to note that Herman herself emphasised the oscillating and dialectical nature of these phases (Herman, 1992b). In practice, the stages of healing from trauma don't always happen in a strictly sequential manner. They can overlap or be repeated at different points during treatment. Also, there isn't strong evidence to suggest that a phased approach, where stablisation has to take place before trauma processing, always works better than just focusing directly on dealing with the trauma itself. Critics argue that stabilisation can be an unnecessary use of clinical time without significantly improving outcomes or reducing dropout rates (Baekkalund et al., 2021; de Jongh et al., 2016; Oprel et al., 2021).

An additional concern raised is that overly emphasising a stabilisation phase in trauma therapy can inadvertently encourage avoidance behavior in clients. The idea behind this concern is that if therapy overly prioritises or prolongs the period dedicated to helping clients feel safe and stable, without addressing traumatic memories and their associated distress, it can reinforce the idea that avoiding those memories is the safest option. Clients may interpret this focus as confirmation that their fear of confronting the trauma is justified and that avoidance is an acceptable strategy.

Over emphasising or prolonging the stablisation phase can stem from several factors, including therapists' empathetic and compassionate tendencies leading to the concern that they may upset the client, therapists’ feeling under-confident, or a misconception that addressing trauma memories may cause harm or retraumatisation (Murray et al., 2022). However, it's crucial to stress that substantial evidence supports the idea that actively engaging with trauma memories, rather than avoiding them, is the most effective approach to treating trauma patients.

Avoiding Overactivation:

Although we do not wish to encourage avoidance of trauma memories, we should simultaneously be vigilant to only activate trauma memories at a pace that is tolerable to the client and can be processed effectively within the time limits of the session. We must avoid overwhelming clients by uncovering too many facets of the trauma memory at once. Instead, we should focus on one aspect or part of the memory during a session before considering addressing other aspects, preventing potential retraumatisation.

There are moments when we, as therapists, need to act as a brake during the session. Sometimes, clients struggle with regulating their emotions, and they might start recounting multiple layers of trauma. This can lead to unresolved issues when they leave the session, as there isn't enough time to address them comprehensively. In other cases, clients may share more about their trauma than they're emotionally prepared to handle at once, often because they believe it's what we expect from them.

Unfortunately, I've seen instances where such situations caused clients with PTSD to disconnect from treatment. They return home to flashbacks, distress, nightmares, and develop the belief that therapy is too intimidating or unhelpful. In some instances, this has occurred despite my best efforts to prevent it, as I may have underestimated the painfulness of certain memories for the client. Therefore, while our goal is to bring these memories to the surface and facilitate a reframing process, it must be done carefully and thoughtfully, ensuring that we only delve into the amount that the client can update and heal during a specific session.

Here are a few strategies that may prove helpful in this regard:

1. Notice Client Discomfort: If a client expresses that recalling certain memories is uncomfortable, emotional, triggers nightmares, or causes other psychological distress, or if they mention that they tend to avoid talking about or remembering a particular memory, take these remarks as cues to exercise extra caution with these memories. It's important to emphasise that this cautious approach isn't about avoidance but rather a means to assist the client in confronting their trauma memories in a supportive and considerate environment.

2. Attentive History Taking: During the client's history-taking phase, be attentive to any memories that appear trauma-related or trigger distress or discomfort. Ask the client questions such as, "How do you typically feel after revisiting or discussing this memory?" If a client indicates that recalling or discussing a memory induces significant distress or mentions avoidance, treat these memories with care.

3. Act as a Gentle Gatekeeper: In such cases, inform your client that while you're eager to hear their story, you are also aware that this memory may be overwhelming to them, and you would like to make sure that at this stage of assessment or treatment, you don’t uncover memories that they are not ready to process. An effective strategy is to ask clients to flag with you the existence of trauma memories but not delve into too many details during that stage. Encourage them to communicate the existence of these memories but to provide only the level of detail that feels comfortable at this stage. Explain that you do need to know if they've experienced certain traumas for a more accurate assessment, but that you don't require all the details immediately. This proactive approach can be crucial, as many clients mistakenly believe they must divulge all the details of their trauma to the therapist at once, which can put them at risk of retraumatisation or disconnection from treatment.

Keeping these considerations in mind, here are some guidelines regarding when and how to employ stabilisation techniques:

Assessing Current Needs: At the start of each trauma-focused session, begin by assessing your client's current emotional state and their readiness to engage with traumatic memories. Ask about their anxiety levels, emotional regulation, and any immediate distress.

External Circumstances: Some clients may be experiencing external life circumstances that contribute to instability, such as house moves, financial difficulties, or ongoing medical or legal issues. It is important to adopt a client-centered approach here, maintaining open communication with the client about their priorities and their capacity to engage in trauma work. An initial goal in therapy could be to focus on supporting them through handling the external circumstances. While some clients prefer to arrive at greater stability around their external circumstances before commencing trauma work, others are happy to get to trauma work straight away. External difficulties shouldn't always be a reason to delay trauma-focused treatment, especially if the client is willing and able to engage in therapy. Additionally, therapists should remain vigilant in cases where clients use a prolonged focus on external circumstances as a way to avoid addressing their trauma.

Gradual Exposure: When the time comes to address traumatic memories, therapists often use a gradual and systematic approach. This involves breaking down the traumatic material into manageable pieces and addressing it step by step, ensuring that the client is well-prepared and has effective coping strategies in place.

Monitoring Emotional Threshold: Continuously monitor your client's emotional threshold during the trauma processing phase. Be vigilant for signs of distress or overwhelm, and be ready to pause or shift back to stabilisation techniques if needed.

Post-Processing Stabilisation: After a trauma-focused segment, reintroduce stabilisation techniques to help your client re-center and manage any emotions that may have been stirred up by the processing.