Emotions: Body-Oriented Therapies

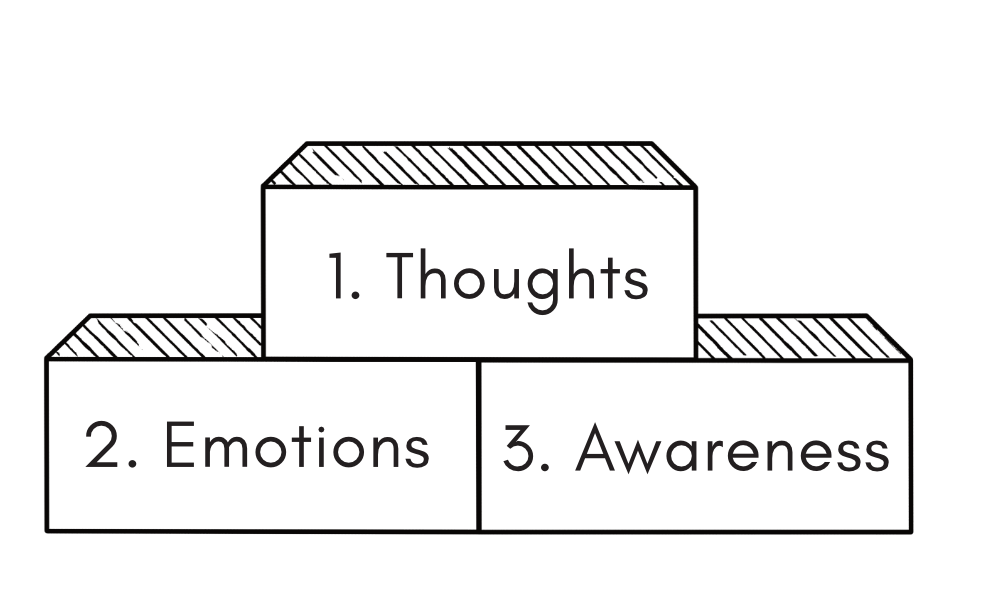

Let's take a step back and revisit the 3 building blocks which we have discussed in previous sections. We have already delved into the first building block, thoughts, and how cognitive reappraisal plays a significant role in reshaping them. In this section we will focus on the next building block: emotions. We will explore how we can work with emotions within the context of therapy. We will learn about the techniques of interoceptive or emotion exposure, which are incredibly promising and exciting areas of therapy and research. The two therapies are very similar in goals and approach and for the purpose of our eCourse, I will be using the terms interchangeably.*

Interoceptive and emotion exposure techniques aim to facilitate the processing of emotions by encouraging individuals to fully experience their emotions and the related bodily sensations in a controlled and supportive environment. They involve systematic and gradual exposure to specific emotional or interoceptive cues, such as increased heart rate, shortness of breath, or muscle tension. The aim is to reduce avoidance and facilitate emotional processing, desensitization, and habituation, as well as the development of adaptive coping strategies and better emotion regulation.

Case Example

A long-term client of mine, let's call her Kelly, attended my practice one day with a return of old symptoms: after a catch up with her brother she had found herself feeling down, unmotivated and struggling to get out of bed for a few days. She couldn't understand why she was feeling this way. It was all very puzzling. Yes, there was a time when her brother's harsh criticisms used to impact her self-esteem. But she thought that was all behind her. Therapy and self-reflection had helped her understand that her brother's criticisms were really not justified. She knew, with no trace of doubt, for instance, that she was a good aunt to her little nephew. Her brother's criticisms following each time she babysat her nephew were, in fact, due to his intense anxiety around parenting his child. She knew that this was not personal. That it was not a sign of her being faulty or not good enough. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) had helped her reassess her thoughts and this had helped relieve her depressive symptoms.

So what could explain this sudden rush of old emotions, which used to be so characteristic of her past self-loathing? She didn't see a logical basis for feeling what she felt.

In the days leading to her therapy session she kept recapping all of her CBT knowledge. Reassessing her negative thoughts wasn't possible. She didn't have any. Well, none that she truly believed in anyway. Reassuring herself with all the rational facts wasn't helping. She still felt just as down and unmotivated.

What Kelly was experiencing was an emotion memory, an automatic response to an old conditioned stimulus. What she was missing was that her current emotion wasn't triggered by a thought or belief. She had already changed those thoughts and beliefs months ago. So there was little point in continuing to meddle with them. Her emotion was being triggered by an external stimulus: her brother, his critical tone of voice and body language, and his specific choice of words (e.g. "I'm disappointed in you"). Kelly's brain had learned to trigger an automatic emotional response every time she was around her brother's criticisms. What did that emotion response feel like to Kelly? Initially, her heart raced faster and she felt a lump in her throat. Then gradually she began feeling tired all over her body, and a heaviness in her chest. These feelings were all too familiar to Kelly as she had felt them many times before. At one stage she used to feel them while having self-loathing thoughts. Now, even though the self-loathing thoughts were gone, she still felt them in her body.

What’s more, Kelly would feel the above emotional response in situations that had nothing to do with her brother. For example, if a friend had a similar body language. Or if she even thought of a memory of her brother being critical towards her or someone else.

Kelly's story is by no means unique. I am all too familiar with new clients complaining of having seen several therapists in the past, with months or years of cognitive based treatment that have not resulted in the emotional relief that they had hoped for. Or if it has, maintaining a 'good feeling' seems to be constant work: keeping on top of those negative thoughts, challenging them on a daily basis, relaxation exercises, breathing and so on.

Of course, when Kelly first attended therapy, changing those negative thoughts and beliefs was crucial. Kelly needed to learn, on a logical, rational level, why she was a worthy human being. She needed to challenge those unhelpful thoughts that had formed the basis of her self-perception. This was the job of cognitive therapy. A job that we have learned, through mountains of research, cognitive therapy does well. Cognitive therapy is necessary. But Kelly's story suggests that on its own, it is not enough.

Fortunately, Kelly only needed a brief recap of her skills in emotion exposure, which she had learned in therapy before. Practicing emotion exposure lifted that emotion and Kelly began feeling her normal vitality, energy and sense of humor.

The Practice of Interoceptive or Emotion Exposure

The following section is…

Please note: the following is an excerpt from the Fount Mental Wellbeing Course.

Copyright © Sahba Saberi 2012

All rights reserved.

Most of us are familiar with the experiences of our emotions, which we normally feel in the body. Let's take a look at a few common emotions and consider how they feel to you. First up, anger. How does anger feel to you?

If your answer was along the lines of 'anger feels like everything is unfair', 'it feels like no one respects you' and so on, you are actually using your thoughts to describe the feeling of anger. The kind of answer that we are looking for is a lot simpler than that. Just pay attention to your body. We are looking for answers like 'it feels like my face is getting hot', or 'I feel a pressure in my throat and chest' and so on. Try one more time. How does anger make your body feel?

And what about the following emotions? Don't forget, you are not describing your thoughts here. You are only paying attention to your body and trying to describe how the emotion makes your body feel:

Fear

Sadness

Shame

Worry

Excitement

Nervousness

Boredom

Disgust

As you can imagine, these emotions could feel different for different people. For example, a person may feel sadness, anger, and anxiety all as sensations in their chest. Another person may call a sensation in their chest 'sadness', but also naming another sensation in their head and a third one in their belly different shades of sadness. They may be felt in different parts of the body, but this person recognises them all as the same emotion. You may have also experienced those times when you feel an emotion, but don't quite know what to call it. What is important to notice here is what the body is feeling, and not so much what we may decide to call that emotion or how we use our thoughts to describe it. To understand our emotions better, it's important to develop a closer connection with the sensations in our bodies, just like the way you became familiar with the taste of an apple in that earlier exercise.

It's also worth mentioning that not all emotions behave the same way. Some emotions are still and stay in one part of the body. Others may feel like a sensation that moves around or pulsates in the body. Some may feel identical to a physical experience. Others are experienced as partly physical, but not entirely!

Some of you may be wondering: what about the advice that you often get, that it's best to not pay too much attention to your emotions? Wouldn't giving them too much attention make us more emotional? Well, if you are sitting in a corner and passively thinking about emotional matters, then yes, you are right. Passively obsessing over issues will not be helpful. Awareness is a different matter. And awareness of the body will help improve your coping with the issues you are facing, not reduce it.

Quality Attention

Some of you may be wondering 'What does it mean to pay attention to an emotion? How do I know if I'm doing it right?' We will try to answer these questions in this section. It is helpful to improve the quality of our attention. So we'll dedicate a bit of time to mastering this seemingly simple skill. First, let's place a little dot on the page…

.

What we will get you to do now is very simple. Just stare at the dot for a while and keep your attention on it. That's it. You don't need to do anything else. Just fix your gaze on the dot for a little while.

How did you go? Were you able to keep your attention there?

Let's try that exercise one more time. If thoughts distract you, gently bring your attention back to the dot and keep staring at it. The longer you can maintain your attention there, the better. And if you can't go very long, that's okay! Practice makes perfect. Let's try again.

.

This is what we mean when we say, 'Keep your attention on the emotion in the body'. It's just like keeping your attention on the dot, except you would be keeping your attention on the part of the body where you feel the emotion. Of course, when it comes to emotions, you won't be using your physical eyes, just your internal awareness.

So, notice what emotion you are feeling in the body, then fix your attention on that part of the body and keep it there as if you are staring right at it and cannot take your eyes off it. Do this even if the emotion is uncomfortable. The discomfort is likely to pass soon. Keep your attention there until the emotion eases. Don't fight the emotion or try to make it go away. You just need to keep your attention on it.

But what about emotions that move around in the body, pulsate, or appear and disappear? How do you keep your attention on moving sensations within the body?

To help you develop the skill of keeping your attention on moving emotions, please view the following video:

What you practised here is similar to what you would do if you are keeping your attention on a moving emotion within your body. Keep your mind’s eye, or your internal awareness, on the moving sensations within your body. It’s best to try and keep your eyes still even if the emotion is moving around in your body.

Perhaps the biggest challenge for your attention is emotions that appear and disappear. This type of emotion is often hard to pay attention to, because as soon as it disappears, we tend to lose focus and get distracted. But then it comes back and surprises us again. But with a little bit of practice we can learn to keep our attention on these types of emotions just as we did with the other emotions. It takes time and patience, but the general rule is, first, give your attention to the emotion. When it disappears, you don't need to do anything special. Just stay focused and ready to look at it again once it returns.

Essentially, what we are saying is that at times it would be helpful to shift your attention away from your chattering and analysing thoughts, and place it on your body. Resist the temptation to stay focused on your thoughts. Keep your attention on your body until it reaches a calmer state. Then you can go back to thinking and see if you still see the problems in front of you in the same way, or whether the new calm body has changed your view of the issues in front of you. Give it a go and see for yourself!

The Science

By now some of you may be thinking, 'Well, it seems to work. But why does it work?' or more precisely 'How does it work?' In this section we will journey into the science of emotion exposure. Although research shows that emotion exposure is effective, there are still a lot of unknowns around exactly how it works. But there are a few theories that try to explain the reasons behind its effectiveness. The first theory relates to a concept called habituation. Habituation is what happens when something is repeated over and over again, and with repetition it gradually loses its impact on you. For example, say you just moved to a new house next to a noisy street. At first the noise feels loud and overwhelming. You can't hear yourself think! But as the hours and days go by, you start noticing it less and less. At some point you barely notice it, unless you pay attention.

Another example is when you wear a new watch for the first time. For some time, you can feel it clearly on your wrist. You notice its temperature, its weight and every other sensation about it. But gradually you stop noticing it altogether. Once in a while, when you think of your watch, you may feel it on your wrist again. But then it goes on to join the many other 'normal' things that you rarely pay attention to.

Most people have heard the story of the boy who cried wolf. It can be said that by repeatedly crying 'wolf', the boy in the story would have habituated the people in the village so that they were no longer alarmed by it.

Usually when we talk about 'getting used to' something, what is really happening is that our brain has developed habituation towards that thing. When habituation takes place, the brain changes at a cellular and chemical level, causing it to become less sensitive to what it has become habituated to. So every time you are habituated, your brain actually changes a little. That's right, there are actual changes to the structure of your brain or its chemicals, that allow your brain to no longer show sensitivity to that thing.

This theory suggests that when we concentrate on our emotions long enough, we get to a point of habituation and that's why we no longer feel that emotion to the same intensity. So, by closing your eyes and keeping your attention on the emotion, what's happening within your brain is very similar to what happened after a few hours or days in that new house in the noisy street. We often don't let this process happen in our brain because we try to distract ourselves from uncomfortable emotions before the brain has had a chance to reach habituation. When you close your eyes and concentrate on an emotion instead of avoiding it, your brain structures and chemicals may be changing and, in turn, what you experience is reduced sensitivity to that emotional experience.

The second theory is that emotion exposure works in a similar way to normal exposure therapy. Remember, classical conditioning means that our brain makes a connection between two unrelated things. And when we perform exposure therapy, we teach the brain that the two things aren't really connected anymore. We do that by facing the things that we fear or dislike and letting our body do the rest! Exposure is an automatic process. We don't need to deliberately teach our body anything.

Similarly, our bodies can be conditioned to react to certain situations, giving us the experience of an emotion. So a date, like the anniversary of a sad event, or a smell, a place, a person or any other reminders might bring back the memory of an emotion for you. Like a heavy heart, a lump in the throat, a funny feeling in the belly and so on. So that smell, that place, that person or the date of that anniversary are now acting like conditioned triggers that bring back an emotional memory.

Sometimes we don't even know what emotion has been triggered. Here's an example. Imagine that today you are feeling upset because you just had an argument with a friend. You go shopping to get it off your mind. You see a perfume bottle, have a smell and spray a little bit on your wrist. As you smell it for the rest of the day, you are conditioning the smell of that perfume to act as a trigger for the emotion that you're feeling. Months later, you walk past a complete stranger that's wearing the same perfume. You might suddenly feel a heavy emotion and have no idea where it came from. You see how confusing the world of our conditioned emotions can get?

As you can see, not all emotions are new and fresh. Many of our emotions are conditioned responses from things that have happened to us in the past. Our bodies react in similar ways in similar situations, creating similar emotional experiences, over and over again. Emotion exposure means that we can clear up the fingerprints of an emotion that belongs to the past. The memory can then be just a memory, rather than a trigger for an old emotion.

It's also worth noting that some of the conditioned emotional memories that we have, go all the way back to our childhood. Pleasant or unpleasant childhood environments can create all kinds of emotional memories. When parents and other caregivers punish or reward children, for example, some powerful conditioned responses can be created. So for example, if a parent used to snap at you or tell you off every time you were having playful fun, chances are that as an adult, every time you are having a good time, you also feel a negative emotion deep down. You then use your thinking to make sense of this and say to yourself 'I'm feeling guilty because I'm wasting time'. Or at times, when people are sensitive to criticism, they could very well be reacting to a conditioned response that was created earlier in their life, when they were in trouble with their parents for making mistakes.

The final theory that tries to explain the effectiveness of emotion exposure is that it facilitates acceptance. As you may recall, acceptance is letting go of our internal resistance and war against the reality of this moment. Emotion exposure and acceptance have a few things in common. Emotion exposure relies on the principle of not expecting ourselves to change, control, resist or fight our emotions. In other words, it increases our acceptance of our emotions, just as they are in this moment. And acceptance can help us cope better with unwanted and uncomfortable realities. In turn we may feel a general state of calmness and peace. You may have experienced this during your practice of acceptance in previous chapters.

Thinking vs. Emotion Exposure

Perhaps the real answer to the question of emotion exposure's effectiveness lies in a combination of these 3 principles: habituation, conditioning and acceptance. Considering these principles can help us make sense of those ingredients that seem to make emotion exposure work most effectively! For most of us, emotions are often there, running amok within the body, day after day. And we are often busy thinking about our problems and the emotions attached to them. So you may say that every day you think about your emotions and wonder why emotion exposure would do anything different or new for you. The answer is that emotion exposure is not the same as thinking about your emotions. There are three main ingredients that distinguish emotion exposure from the way that we normally relate to our emotions.

1. Awareness, not thinking - emotion exposure is all about bringing our attention to the body, or to the experience of our emotions. It is a mindfulness practice. The focus is not on analysing the emotions or thinking about them - thoughts like 'What is this emotion?', 'Where does it come from?', 'I’m tired of always feeling down’, 'What if something bad happens?', and so on. When practising emotion exposure we take a break from thinking and instead notice what the body is doing. Or what the experience of that emotion feels like.

2. Sustained attention - we normally only give quick short-lived attention to our emotions, and our attention is weak and divided as we go about our day or are distracted by a million racing thoughts in our head. Focusing your attention on the emotion and keeping it there a bit longer than usual may be what is needed to allow habituation to be achieved, or to make exposure therapy most effective.

3. Acceptance - in other words, giving up the temptation to change the emotion. This is very important. When practising emotion exposure, you are only a passive watcher. You are not trying to change, soothe or escape. The more you give up the temptation to control your emotion, the more quickly it will pass. Imagine getting on a roller coaster. Once you are on the ride, it is not your job to control it or stop it. And you could not do that even if you tried! You just need to sit back and let the ride take you wherever it takes you. Trying to control it is pointless. When practising emotion exposure, we need to treat our emotions in exactly the same way. We cannot control or get rid of emotions using will power. That only results in more internal anguish and distress. So we might as well sit back and experience the ride.

Remember, this is not a process that you can speed up using your will power. So as you have your eyes closed and are feeling the emotion, be mindful of thoughts like: 'When is it going to go away?', 'How can I get rid of it?', 'This is pointless', 'It's not working' and so on. These thoughts are an indication that you are placing your focus on trying to get rid of the emotion, rather than on feeling the emotion and experiencing it fully.

An Onion

At times, our emotions are like an onion. If you peel off a layer of the onion, there will be another one underneath it. And another one. And another one. After some time, the layers will stop and you will end up with no more onion. Similarly, at times during emotion exposure you will find that, as an emotion leaves, there is another one underneath it. And another one underneath that one. It may feel like the layers of emotion will never end, and that all you are doing is replacing one layer with the next one. But continuing to practise emotion exposure means that at some point the layers may end, allowing you to experience a calm, peaceful space of no emotion.

It may help you to remember a rule:

— Thinking often brings up emotions (new emotions or old ones)

— Emotion exposure allows the emotions to be alleviated

So you may find that at times when you begin thinking, you begin feeling more emotions. If this happens, practise emotion exposure on the new emotions that are activated. Remember to get into the habit of pausing your thinking and focusing on the body instead, because getting lost in thoughts may result in more and more emotions coming to surface. However, as each emotion lifts up, feel free to allow your thoughts back in again. So allow the thoughts in, and once you feel an emotion, stop thinking and focus on the body. Repeat this process until you feel lighter and more at peace.

Note: don't forget to check for any errors in your thinking as well. If a thought error keeps creating an emotion for you, it's important to first realise the thought error and change your thinking.

Challenges with the Practice of Emotion Exposure

The challenge of practicing emotion exposure is not going to be the same for everyone or for every emotion. You might find that certain emotions are more challenging to work through or concentrate on. Others are a lot easier. At times, practicing it will result in quick relief to your emotions. At other times it might not work so quickly or smoothly. What is important is to not give up when you face a challenge, but to keep trying. Check that you are correctly applying all the principles that you have learned in this session. Here are 7 common challenges that people report when practicing emotion exposure, and tips on how to deal with them:

1. 'I feel an emotion, but I can't find it in my body' - If this applies to you (and it's one of the things that most people experience from time to time), then don't try so hard to pin the emotion down in your body. Just concentrate on the general experience of the emotion. The overall feel of it. The feeling that the emotion gives you. Sit with that experience and keep your attention still. At some point, you may start noticing it within the body as well. If that happens, start keeping your attention on that part of the body.

2. 'I'm feeling a few different sensations, in different parts of my body all at the same time' - it's best to focus on one part of the body at a time. Maybe start with the one that you're feeling most strongly, or the one that keeps grabbing your attention. Once that sensation lifts off, move on to the next. The reason that we suggest this is that the more intensely you focus, the quicker you will get results. So, if your attention is jumping between different parts of your body, it might at times reduce its effectiveness. But, if focusing on only one part proves difficult, then try staying aware of all the different sensations appearing and disappearing within your body, as if you are watching a show. Keep your attention on the show until the feeling calms down.

3. 'I am feeling a sensation in my body, but I'm not sure if it's an emotion or just physical?' - It is not always easy to tell emotions apart from purely physical sensations. That's one reason why, when our bodies are unhappy, (e.g. when we are hungry, tired, coming down with a cold and so on) we are more likely to feel intense emotions. The key here is to stop getting bogged down with the question 'is it an emotion or just the body?' and instead practise emotion exposure on it anyway. If what you are feeling in the body has an emotional component, you should experience relief after some time. But that said, if you are certain that there is a physical component, attend to that as well. If you are hungry, eat something. If you are tired, make sure you get some rest. If you are sick or in pain, speak to a doctor. The bottom line is that the body and emotions are so intertwined, that they regularly impact each other. For example, pain can intensify your emotions, but emotions can also intensify your pain. So it is best to work on both.

4. 'I'm feeling bored, restless or tired. What do I do?' - Boredom and restlessness are also emotions. Notice how they make your body feel and practise emotion exposure around them. Tiredness can be physical or emotional. If you believe it may be emotional, try practising emotion exposure on the parts of the body where you feel it.

5. 'What happens if emotions come up in situations where I can't close my eyes and focus? How do I deal with that?' - With continued practice, you can start noticing your emotions even as you go about your day and with your eyes open. Notice how in social situations, as painful emotions arise within your body, you actively try to push them away and ignore them. Instead, stay with the pain in the body and place your attention on it, until it subsides. If, at times, you need to focus more, find a quiet corner (e.g. take a toilet break!) and practise emotion exposure. Alternatively, work on any left-over feelings from the emotion at the end of the day, when you get home or when you find some alone time. As you work through these emotions, you may notice that they return with less and less intensity over time, or that some emotions never return again.

6. 'The emotion that I'm feeling is too uncomfortable. I find it too painful to pay attention to. What do I do?' - It is unfortunate that some emotions can be so uncomfortable. It often feels easier to put them in a box and forget about them, like Jasmine did with her monster. But with a bit of determination you may be able to reduce the discomfort of these emotions as well. Here are a few things you can try:

— Use your imagination to picture yourself yelling, screaming or expressing the emotion however you would like to express it. Or consider expressing yourself while writing or creating art. Now feel the emotion in the body as you express yourself.

— Imgine a scenario where the emotion is changed. Picture your life situation improved. Or if the emotion is from the past, imagine a scenario with a happier ending. As you imagine these things, keep your attention on the body and feel all the sensations that are happening. Feel the relief as well as any left over emotions.

— Talk to someone. Seek therapy from a trained professional, or find a friend who will not rush you to get rid of the emotion using logic, and ask them to allow you to express what you're feeling. It may be helpful to let them know that the purpose of speaking to them is just so you can express your emotions. Now, just talk it out as you feel the body at the same time.

— Focus on one sensation at a time, as we discussed in the 2nd point above. Once you find a painful sensation in your body, don't get distracted by other sensations or thoughts. Just fix all of your attention on it and keep your attention firmly on that part of the body until the sensation is relieved. Now look for other sensations.

— Chip away at it - look at the emotion a few seconds at a time, and then if it's too painful let it go. Do the same again next time. Gradually, by repeating this, the monster will feel less and less scary and you will be able to keep your attention on it for longer.

7. 'My attention is wandering and I am too distracted. How do I concentrate on the emotion?' - It may be a good idea for you to place your focus on mindfulness of thoughts to begin with. As you practise sitting there and watching your thoughts, remaining aware of their movements, it may help to consider this analogy, which we've touched on before:

Imagine you're standing in a river with waves of water washing against your legs. Imagine your thoughts and emotions to be like the water. Your job is to stay aware of the water (i.e. thoughts and emotions) as they come and go. Do not think, analyse, try to create the current or stop the current. Just stay aware and let it flow. Practise this as often as you can. You may find that this practice gradually helps your thoughts to slow down and for you to become more mindful of your thoughts and emotions.

Finally, please remember that emotion exposure can be a boring practice! Mindfulness in general may feel boring. That is okay. Being bored is not something to be afraid of. In fact, we suggest that you expose yourself to 'boring' and push through it. So if you are feeling bored focusing on a boring sensation within the body, just tolerate it and keep your attention there anyway. At some point you may find that boredom gives rise to a sense of peace and calm. So this will be worth the effort!

Therapeutic Decisions: When to Address Thoughts and When to Practice Emotion Exposure?

In the realm of therapy, a common dilemma often arises when determining the most effective approach to address a client's concerns: should one focus on reshaping thoughts through cognitive reappraisal or delve into the underlying emotions through emotion exposure? The decision hinges on a variety of factors, including the client's unique presentation and the nature of their distress.

**Starting with Cognitive Reappraisal:**

As a general guideline, when cognitive distortions or unhelpful thinking patterns are apparent, it's often beneficial to begin by addressing these cognitions through cognitive reappraisal techniques. This approach involves identifying and challenging irrational or negative thoughts and replacing them with more balanced and realistic perspectives.

However, it's vital to emphasize to clients that the cognitive strategy, while powerful, might not instantaneously eliminate all associated emotions. It's not a magic wand that makes all distress disappear. Setting realistic expectations in this regard helps clients understand the limitations of cognitive work, preventing potential disappointment and reducing the pressure to 'feel better' immediately.

**Transitioning to Emotion Exposure:**

Once cognitive errors have been identified and addressed, the therapist can then pivot towards exploring and processing the underlying emotions through emotion exposure techniques. However, there are situations where it's more appropriate to initiate therapy with emotion exposure:

1. **Client Struggles to Identify Triggers or Cognitive Causes:** In some cases, clients might find it challenging to pinpoint specific triggers or cognitive reasons for their emotional distress. This could be due to a lack of self-awareness or a deeply rooted emotional issue that resists easy categorization. In such instances, it's often more practical to commence with emotion exposure to access and work through these complex emotions directly.

2. **Prior Cognitive Work:** If previous therapy sessions have effectively tackled cognitive barriers, and the client still presents with persistent and overwhelming emotions linked to a particular issue, shifting the focus to emotion exposure is advisable. This transition ensures that therapy continues to progress and evolve to meet the client's evolving needs.

In essence, the choice between cognitive reappraisal and emotion exposure isn't rigid but rather adaptable to the client's circumstances. Therapists must remain flexible and attuned to the client's unique situation, selecting the approach that aligns most effectively with their current needs and the underlying complexities of their emotional experience. By navigating this therapeutic dilemma thoughtfully, therapists can offer tailored interventions that promote emotional healing and growth.

Incorporating Imagery Work

Imagery exercises offer a powerful and versatile tool in therapy, especially when combined with emotion exposure techniques. These methods can be applied in two key ways to facilitate clients' emotional processing and healing.

1. Practicing Emotional Exposure in Challenging Scenarios:

Scenario Visualisation: In situations where clients grapple with specific emotional challenges like social anxiety, imagery exercises can be employed to help them imagine scenarios that typically trigger distressing emotions. For instance, a client dealing with social anxiety may envision themselves in various uncomfortable social situations, such as public speaking or attending a social gathering.

Emotion Exposure: Following the scenario visualization, clients can then practice emotion exposure techniques centered on the sensations within their bodies. Encourage clients to fully immerse themselves in these imagined situations, paying close attention to the physical and emotional responses that arise. This could include observing racing heartbeats, sweaty palms, or feelings of dread.

Gradual Desensitization: The goal is to gradually desensitize clients to these emotional triggers through repeated exposure. Over time, as clients continue to imagine and engage with these emotionally charged scenarios while practicing emotion exposure, they can begin to build tolerance and find the imagery of the situation more tolerable. This process can help reduce the intensity of their emotional reactions in real-life situations.

2. Childhood Work and Emotion Exposure:

Revisiting Childhood Memories: Another valuable application of imagery exercises combined with emotion exposure is in childhood work. Clients are encouraged to revisit memories from their early years, particularly those marked by emotional turmoil or distressing experiences.

Cognitive Reappraisal: Initially, imagery exercises can be employed to facilitate cognitive reappraisal. Clients are guided to reimagine these childhood scenarios and engage in cognitive work that helps them reframe and make sense of their childhood experiences from a more adult perspective. This step aims to provide insight and understanding.

Emotion Exposure in Childhood Scenarios: Subsequently, clients can revisit these same childhood memories but now focus on the emotional aspect. They are encouraged to immerse themselves in the memory, paying close attention to the physical sensations and emotions that emerge. This process allows clients to practice emotion exposure, where they embrace and process the emotions associated with these past events.

This combination of cognitive reappraisal followed by emotion exposure within the framework of imagery exercises can be remarkably transformative. It enables clients to gain deeper insights into their emotional responses, providing a pathway for healing and growth. Moreover, it empowers clients to develop healthier coping mechanisms and navigate challenging emotions with increased resilience.

As with any therapeutic technique, it's essential to tailor these approaches to each client's unique needs and progression. Encourage open communication throughout the process to ensure that clients feel safe, supported, and empowered on their journey toward emotional well-being and healing.

Therapist Anxieties

Therapists often approach interoceptive exposure (IE) with caution, employing relaxation, breathing, or appraisal exercises to alleviate its perceived discomfort. However, emerging research challenges these preconceptions and suggests that IE, when used in isolation, is not only tolerable but also effective in diminishing anxiety sensitivity (Deacon et al., 2012). Therefore, therapists are encouraged to embrace emotion and interoceptive exposure techniques without reservation. By integrating these approaches into their practice, therapists can offer targeted interventions that directly engage with the fundamental mechanisms of emotions, promoting more efficient and focused therapy.

The Therapist's Practice of Emotion Exposure and its Benefits

The practice of emotion exposure offers therapists substantial advantages when integrated into their professional routines. While it serves as a valuable self-care tool, it also has the potential to achieve the additional objectives of mitigating countertransference, addressing emotional contagion, and enhancing therapists' comprehension of their clients.

Emotional contagion, the phenomenon where one person's emotions and related behaviors can trigger similar emotions and behaviors in others, is a recognised aspect of human interaction. In the context of therapy, emotional contagion can result in countertransference, where a therapist unconsciously takes on the emotions and reactions of their clients, potentially interfering with the therapeutic process. As therapists, it's crucial to be aware of our emotional responses to clients and to use this awareness as a tool for growth and understanding.

There have been instances when certain clients triggered specific emotional reactions in me. Mindfully exploring and working through these emotions not only assisted me in gaining new insights about the client but also deepened my understanding of how to best support them. Allow me to share a couple of illustrative examples:

Example 1:

On several occasions, I found myself feeling perplexed when working with particular clients. Despite having well-thought-out treatment plans, I would enter sessions only to be overtaken by confusion, forgetting my intended strategies or the starting point for our discussions. This pattern persisted consistently with these clients, prompting me to inquire into its origins. As I engaged in emotion exposure centered around the emotions tied to my confusion, a remarkable revelation emerged: my clients frequently exhibited parallel patterns of confusion and mental disorganization. Attending to my vicarious emotional response not only provided valuable insights into my client's psychological state but also enabled me to regain my focus and composure within these sessions.

Example 2:

Certain clients with histories of childhood abuse often reported ongoing mistreatment in their daily lives. During interactions with these clients, I occasionally experienced heightened emotions, including anger, frustration, or an inclination to react harshly to various behaviors. While some of these behaviors might have appeared reasonable grounds for such emotional responses, the intensity of my reactions stood out. Furthermore, similar behaviors displayed by others did not consistently trigger the same emotional responses within me. Recognizing this divergence led me to explore my emotional reactions through emotion exposure. What I uncovered were patterns of abuse that had given rise to unhelpful emotional responses in these clients, including anger, a sense of victimhood, and an overcompensatory entitlement. By attentively exploring my own emotional reactions, I not only gained a deeper understanding of my clients but also managed to circumvent the customary angry reactions they often faced from society. Instead, we could collaboratively address their unhelpful behavior and help them comprehend why they seemed to attract mistreatment.

In cases where clients were ready, I shared with them my emotional reactions in response to their behavior, using a specific analogy to facilitate their understanding. I likened the emotional residue of past abuse and unhelpful environments to the lingering smell of smoke on clothes after exiting a smoke-filled room. In the same way, individuals who have been surrounded by abuse or bullying tend to carry emotional remnants from those environments, which others can subconsciously pick up on and react to. This, I emphasize, is not the client's fault but may help them make sense of their recurring experiences with people.

By engaging in emotion exposure personally, therapists can gain a deeper understanding of their clients' emotional experiences and cultivate greater empathy, which ultimately enhances the therapeutic process.

* Disclaimer: I use the terms emotion exposure and interoceptive exposure interchangeably. Although there are small differences between the two therapeutic techniques, there is significant overlap between these therapies and I have elsewhere argued that the two should be considered synonomous. Additionally, you may notice that I preference the term emotion exposure over interoceptive exposure because when speaking to the public, I think there’s value in keeping the language simple and accessible. Especially if we want to be accessible to kids and adolescents. Everyone has an idea of what emotions are, but a term like interoception needs definitions and a level of academic interest from our audience.