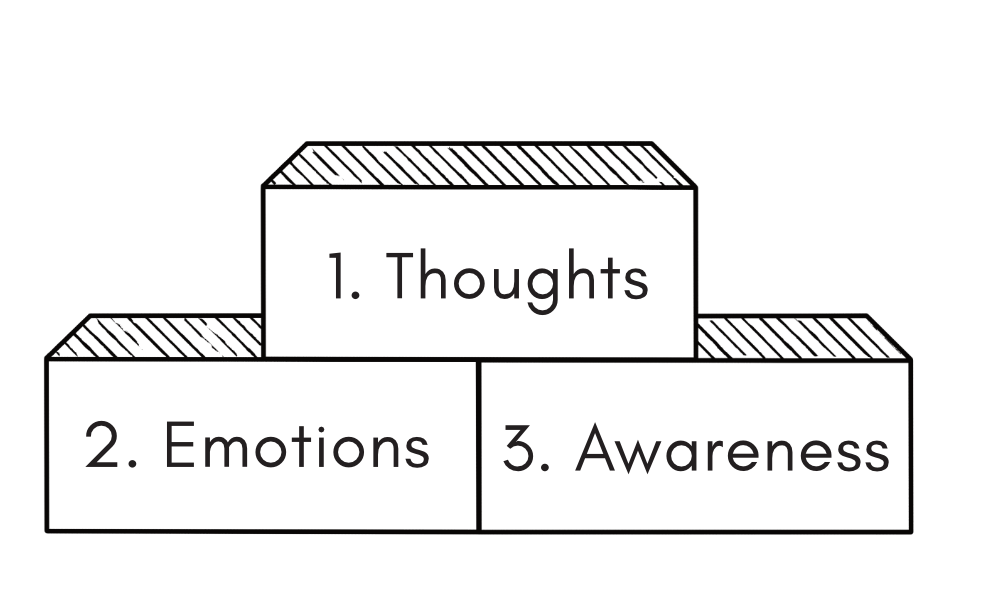

The 3 Building Blocks

First, let's learn about an important principle which is at the core of the Fount model. Based on this model, there are 3 building blocks that constitute our psychological existence: thoughts, emotions, and awareness. Although in principle we are all well familiar with these 3 building blocks, but you may be surprised to find that in practice, most of us can struggle to differentiate between them. And I’d like to suggest that learning to differentiate between them is at the core of successful clinical practice. Let's take a closer look at each.

1. Thoughts

Let's begin with the first building block: thoughts or cognitive elements. Picture this - thoughts are like an internal conversation, a cinema screen in our minds, or even a sports commentator providing commentary on everything as we go about our day. They are formed from words, images, or ideas. From analyzing and judging things to planning and coming up with new ideas, thoughts are the general activities of the mind. And when I say the word ‘activity’, I need to highlight that word. Thoughts are about doing. They are the act of using logic, rationality, and imagination, naming, comparing, categorising, judging and so on. I would like to invite you to take a moment to watch your thoughts, or listen to your internal dialogue. It may help to close your eyes, bring your attention inward and pay attention. See if you can get to know your own thoughts for a minute. I suggest you pause the audio and try it now.

2. Emotions

Now, let's move on to the second building block: emotions. Unlike thoughts, emotions are not based on language. Instead, they are pure experiences, much like the taste of an apple - something that's hard to put into words. You could try to describe how an apple tastes to someone who’s never had an apple before, but they could never quite understand the taste of an apple until they’ve tried it for themselves, right? Because experiences are not language based. They need to be felt and experienced. Language can’t communicate them effectively.

We often feel emotions somewhere in our bodies, like a racing heart or trembling knees when scared, butterflies in the belly when anxious or excited, heaviness in the head or eyes when feeling down, or the heat of anger. At times emotions are still. At other times they are restless and chaotic, moving, pulsating, or appearing and disappearing. We don’t always know that we are feeling an emotion, or what kind of emotion we are feeling. At times, the emotion can feel purely physical and somatic.

Try to take note of your emotions for a minute. It may help to close your eyes. See if you can scan your body for a minute and notice any emotions that you may be feeling right now. You may like to pause the audio to give yourself as much time as you need.

Another feature of emotions is that they can be pleasant or unpleasant, but thoughts, on their own, do not carry such inherent qualities. For example, you can have a thought ‘I’m not good at playing the piano’ without any emotional attachment. It’s just a thought, an understanding that I’m not good at playing the piano. But the same thought could have an emotional attachment for someone else. They could feel sad or upset about not being able to play the piano well. In that case, the thought and the emotion may happen concurrently, but still they can be seen as qualitatively different. The Fount model emphasizes the importance of recognizing the fusion of thoughts and emotions and yet recognise their qualitative distinction.

3. Awareness

Lastly, let's explore the third building block: awareness. Often confused with thinking or emotions, awareness is entirely different. Similar to emotions, awareness is not composed of words and sentences. It is the simple act of noticing things, like looking, listening, tasting, smelling, and feeling.

As humans, we tend to quickly start thinking about whatever we notice. Imagine seeing a pink flower; initially, you simply notice its shape, color, and smell. But then your thoughts may soon follow, like, ‘I like this flower, but I like red flowers better,’ or ‘I wish my partner would surprise me with flowers.’ Again, although thoughts and emotions may arise soon after noticing, they are qualitatively different and it is helpful to be able to differentiate between them. The act of noticing and becoming aware is also what we call mindfulness.

Let’s do an exercise to help with noticing awareness. The following section is an excerpt from my book Mind Wellbeing.

“Pick up an object and hold it in your hand. It can be a pen, a book, a spoon, a flower etc. First spend some time thinking about this object. Notice that your thoughts are made up of words. They may look like this:

'This is a nice looking pen. I like the shape. But it doesn't write so well. My other pen writes better. I wonder where it was made. Is it cheap or expensive? I should write with the other one though, it's nicer to write with.' And so on.

Notice your thoughts as they take place.

Now spend a bit of time just looking at the object. No thoughts. No commentary. Just look at it. And feel how it feels in your hand. Maybe smell it. Notice the object, with all its little details, with all of your attention.

This is called awareness, or the act of mindfulness.”